Dr James Barry was an Irish military surgeon who in 1826 successfully performed a caesarean section where both mother and child survived, an extremely rare and high-risk feat at the time. Barry had a successful and well-respected career until after his death, when his biological sex was discovered and his work was placed under scrutiny and suspicion*. We take a closer look at the gender-defying doctor whose work in female healthcare revolutionised the diagnosis of crural hernias.

Dr James Barry was born 1789 in Cork, Ireland. However, James Barry was not the name he was born with. James Barry was named Margaret Anne Bulkley, having been assigned female at birth.

In 1809, Margaret started a new life with a new identity as James Barry and moved to Edinburgh to enroll as a medical student at the University. This was no small feat – Edinburgh was deemed the finest place to study medicine at the time. Barry qualified as a doctor in 1812 and moved to London, where he worked at St Thomas’s Hospital for several months. In 1813 he enrolled as an army surgeon and travelled all over the world, including the West Indies and South Africa.

North Front of the Royal Infirmary at Edinburgh (Circa 1751) Sandby, Paul. University of Edinburgh.

Barry’s work suggests he was an advocate for the ‘fairer sex’, having dedicated much of his work and research to women’s health. He had a vested interest in STI treatment, female sexual health, midwifery, obstetrics and gynaecology.

Barry’s interest in female healthcare started at university with his thesis on hernias – with a specific focus on hernias in women. He was one of the few doctors of the time who warned against the hazards of hernias in relation to pregnancy and childbirth.

Dr Barry, whose own gender could be considered ambiguous, dedicated his thesis to a medical condition that led to the discovery of past mistakes in defining and identifying gender. Some people are born intersex, meaning that their biology doesn’t fit the typical characteristics of male or female anatomy. For instance, they might be born with both testes and ovaries, or have a combination of XX and XY chromosomes. In Barry’s day, if someone was born appearing mostly female but possessed one or two testicles, they were often misdiagnosed as having a hernia. Patients also misdiagnosed themselves as having developed a hernia and would not find out they were intersex until much later in life, or until they were married and struggled to procreate.

Some patients diagnosed as intersex saw this as a lucrative opportunity to begin a new life. Born in 1798 and christened as Marie Rosine Göttlich, Marie’s sex came under suspicion after medics concluded Marie’s self-diagnosed double hernia was actually a pair of descended testicles. After this discovery, Marie was ordered to change their name to Gottleib and although intersex, took on a new identity and had a new legal status as a man. The new Gottleib Göttlich took this as an opportunity to start a new career and travel around Europe by offering themselves to medical schools for examination to help physicians learn more about intersex anatomy.

Barry’s research focused heavily on the female pelvis as well as the abdominal regions intimately connected to the reproductive organs, and paid particular attention to crural hernias (more modernly known as a femoral hernias), which is a type of hernia that occurs in the groin area and are found more commonly in women. His thesis explored the relation between the vagina and crural hernias, where Barry warned against the implications of childbirth, especially for mothers who have a crural due to the risks of tearing and rupturing the hernia.

Barry also warned against female fashions, particularly corsets, and hobbies such as horse riding. Barry viewed them as social triggers of hernias and complained, in the case of corsets, that tightly pulling the laces caused internal organs to be displaced, adding pressure onto the hernia which can lead to the tearing of the abdominal wall. Although critical of female dress, his warnings and advice suggest Barry continued to prioritise the welfare of women.

In Cape Town, South Africa, Dr Barry was promoted to Medical Inspector, which was the second-highest medical office in the British Army. There he helped improve living conditions for British soldiers as well as local civilians, through bettering access to clean water, cracking down on quack doctors and creating clear rules for the humane treatments of those in leper colonies.

It was during his work in South Africa in 1826 that Dr Barry successfully performed one of the most notable and defining moments of his career. Barry successfully performed a successful caesarean section, rarely achieved by surgeons due to high fatality risks.

Caesarean sections (commonly referred to as C-sections) have been performed since the time of Ancient Greece and Ancient Rome. In the 19th century, performing a C-section still remained an enormous accomplishment, due to the risk of infection, low success rates and lack of experience. Due to high mortality rates no narratives exist from mothers who had C-sections before the 1500s. C-sections would have been traumatic; typically, a surgeon was called to perform a fetal craniotomy, damaging the foetal skull and disposing of the baby in the hopes of saving the mother. C-sections were sometimes performed to save babies whose mothers were dying or died from childbirth. In most cases, it was rare for surgeons to ensure both mother and baby survived the procedure.

At this point in his career, Barry had not even witnessed a caesarean, and it’s possible the only practice he may have had would have been a post-mortem C-section. Although under pressure and with the odds stacked against him, Dr Barry was successful in delivering Wilhelmina Munnik’s baby, keeping both mother and baby alive. It has been suggested, due to Barry’s interest in female reproduction and childbirth, that Barry had been thinking about the childbirth procedure without the baby passing through the birth canal for quite some time. This is perhaps why Dr Barry’s procedure was so successful: his attempt was not a rushed one to remove the baby to keep the mother alive, but rather a premeditated attempt with the purpose of ensuring the lives of both mother and baby. Barry performed this surgery a century before the procedure became a standard medical practice.

A further notable achievement was Barry’s publication of his research on potential treatments for the sexually transmitted diseases syphilis and gonorrhoea. This new treatment focused on the use of a plant native to Cape Town, the Arctopus echinatus (flat thorn), as Barry was able to study native and local medicines during his time in Africa.

He went on to work in many places across the world and had a distinguished career in the army. During his travels he had a famous ‘run in’ with none other than Florence Nightingale in Crimea. Dr Barry was obsessed with hygiene and seemingly was not impressed by Nightingale’s standards at Scutari Hospital. Barry publicly chastised her, sparking an intense and icy reaction from Nightingale, largely due to being reprimanded in front of her own subordinates, and the pair did not see eye to eye. This little entanglement shows that AFAB* individuals in the patriarchal world of medicine aren’t inherently allies to one another, and Dr Barry and Florence Nightingale certainly made no plans to improve their relationship. Barry retired from his work in 1859 and settled back in Britain.

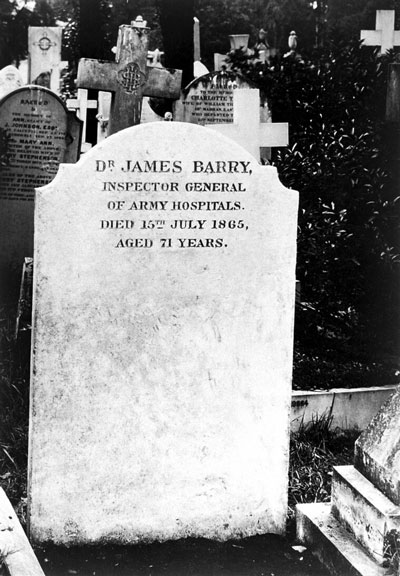

James Barry died of dysentery in 1865 and had left strict instructions that he should be placed in his coffin in the clothes he died in, but it was deemed better to bury him in clean and smart clothes. It was upon his deathbed, when Dr Barry was undressed, that it was discovered he apparently had the biological body of a woman.

Dr. James Barry’s headstone, Kensal Green Cemetery. Source: Wellcome Collection.

Naturally, there was some ambiguity around Barry’s body. James Barry’s servant, Sophia Bishop, speculated that he was in fact a “perfect female” and that there was evidence upon the body of having had a child at a young age. Dr McKinnon, a surgeon and long-term friend to Dr Barry, claimed that Barry was possibly intersex. Despite these findings being passed onto Registrar General Graham, he decided to leave Barry’s death certificate unchanged and officially stated that he was male.

Many historians and those within the medical profession have sought to discredit Dr Barry due to the ambiguity of his gender and draw attention away from the incredible work he did. Regardless of how Dr Barry identified, it does not affect the legacy of what he achieved as a surgeon.

As Dr McKinnon once stated, “It was none of my business whether Dr Barry was male or a female…nor had I any purpose in making the discovery.”

Dr Barry should be celebrated for his incredible feats as a surgeon, his innovative research in hernias and for improving the lives of many across the world.

*This article uses he/him pronouns to describe Barry. Although we cannot know for certain how he would have identified himself privately, he lived his adult life and presented to the world as a man with male pronouns, so we chose to follow that here.

*Assigned Female at Birth