By Jen Wright, Hidden Histories Researcher

In response to the plague of body snatching that had swept the country in the early 1800s, and the risk of prosecution facing Anatomists, an 1828 Report by the Select Committee on Anatomy laid the foundations for new legislation that would put an end to these issues.

A more reliable, and legal, source of bodies for dissection had to be found, but it would be at the expense of the poorest and most vulnerable people in society. Four years later, this would come to fruition with the passing of the controversial Anatomy Act.

The first draft of the Act was opposed by many, but after some deliberately vague amendments to the wording, it finally passed into legislation in 1832.

The new Act allowed anybody with “lawful possession of the body of any deceased person… to permit the body… to undergo anatomical examination” (i.e. dissection), if unclaimed 48 hours after death. Although the wording of the Act had changed, the intentions behind it hadn’t. The main sources of these unclaimed bodies would be prisons, hospitals, asylums, and workhouses.

In effect, workhouse masters had possession of the bodies of any who died there (unless the inmate had specifically ‘opted out’ prior to death), and were under no obligation to notify next of kin of the death, making sure the bodies went unclaimed and could be sold on for dissection. Even if the family or friends of the deceased were notified, by claiming the body they would be liable to pay for burial, which for most in this situation would be an impossible burden.

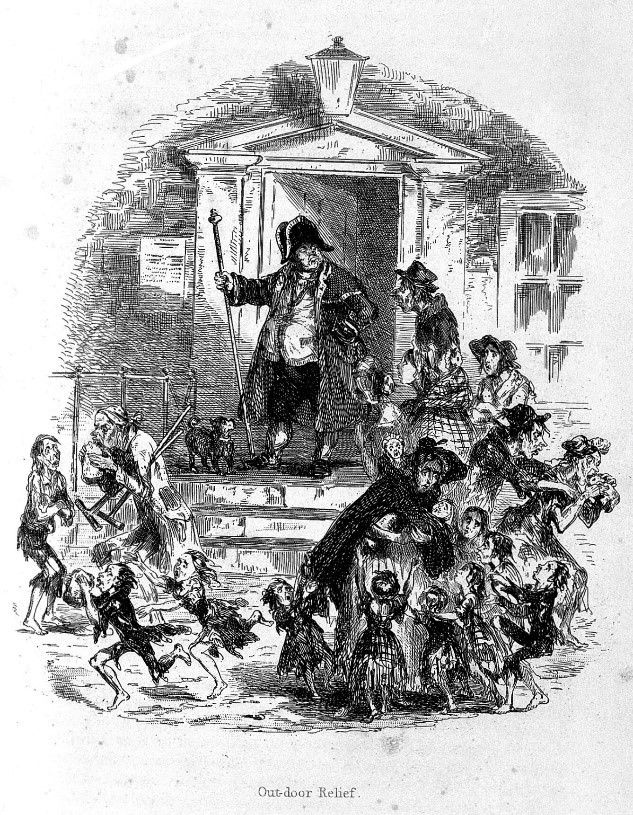

There had been a parish workhouse in the centre of Leeds intermittently since 1638, reopening in 1726 for “Keeping, Lodging and Maintaining the Poor” just after the passing of the so-called ‘Workhouse Test Act’, which allowed parishes to deny poor relief to those who refused to enter the workhouse – in effect a ‘test’ of their need and desperation. Workhouses of the 18th century reimagined social care and brought under one roof many of the roles which had previously been filled by ‘Outdoor Relief’: care of the sick and elderly, training of pauper children, and provision of labour for the unemployed.

The Leeds workhouse had a much larger capacity than others in the county, being positioned at the centre of the rapidly growing industrial area of the West Riding. The majority of inmates were the physically vulnerable, in need of care rather than correction, primarily the very young or very old. This was a particularly turbulent period of time in Leeds. Between 1801 and 1850, the population of the city trebled, and conditions in the poorest parts of the city led to deadly outbreaks of disease, with a cholera epidemic in 1832 leading to 702 deaths.

The Anatomy Act was a fierce political issue in Leeds, and the workhouse trustees agreed “to oversee the distribution of workhouse corpses to Leeds anatomists”. However, those who were opposed to the Act posted notices in the workhouse wards to notify occupants of their potential fate, and inform them “how to prevent their bodies being given to the schools of anatomy for dissection…”. It seems that those residing in the Leeds workhouse may have been more aware than most of what their fate might be – and how to avoid it. Indeed, in the first few years after the Anatomy Act passed, Leeds anatomists still experienced a shortage of bodies.

In 1858-61 the new Leeds Union Workhouse was built at Beckett Street, then on the outskirts of the city, to accommodate 784 ‘inmates’. A few years later, it seems the Anatomy Act had begun to serve its purpose; the 1865 Leeds School of Anatomy prospectus claimed that “the supply of cadavers for dissection continues to be steady and abundant”, and the Union Workhouse master had been paid five pounds to promote the supply of bodies to them.

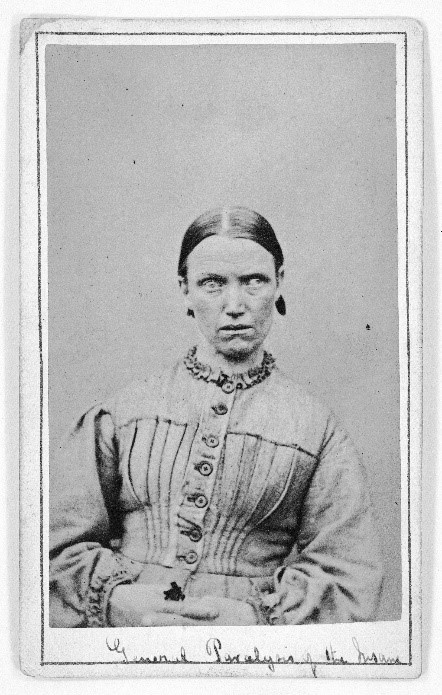

One of the victims of the Anatomy Act in Leeds was Ann Murray, who was an inmate at the Leeds Union Workhouse at the time of the 1881 census, likely following the death of her husband Matthew several years earlier. Although she died in 1883, Beckett Street Cemetery records show Ann was not buried until February 1884, her body coming “from the Medical School”. We can assume this means she was unclaimed after death and was handed over for dissection before burial.

Next time you visit the museum, why not cross over the road and view the ‘Guinea Graves’ – dating back to the 1850s and believed to be the largest collection in the country. Here, those with little money could bury their loved ones in a communal plot with a shared gravestone. Who knows how many of their bodies might first have been passed between the Workhouse and the Anatomists before finally being laid to rest.

Jen Wright, Hidden Histories project participant

IMAGES

- The anatomy act, 1832 ; the pharmacy act, 1852 ; the pharmacy act, 1869 ; the anatomy act, 1871. Public Domain Mark. Source: Wellcome Collection. https://wellcomecollection.org/works/nfrrb8h8