Written by Ross Horsley, Volunteer Coordinator

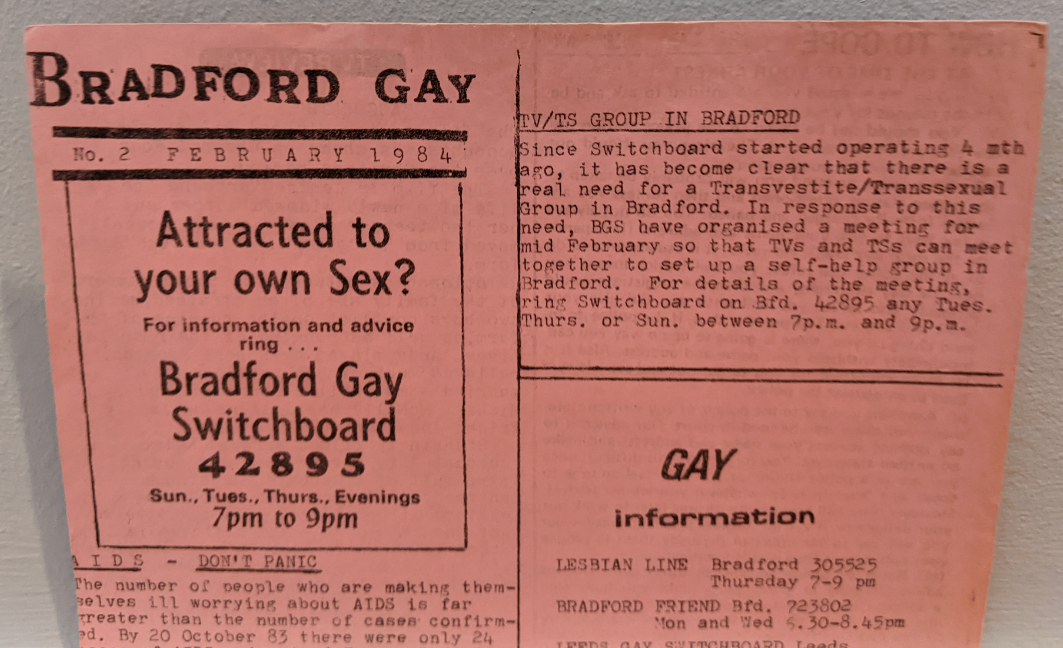

The number of people who are making themselves ill worrying about AIDS is far greater than the number of cases confirmed. By 20 October ’83 there were only 24 cases of AIDS – Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome – in Britain… although there is obviously reason to be concerned, we must not relate to AIDS as “our disease”.

Bradford Gay Newsletter, 1984

Nearly four decades later, these words from the front page of the Bradford Gay newsletter of February 1984 seem, oddly, both naive and prescient. At a time when AIDS was strongly linked in many minds to a mysterious outbreak in faraway New York, the threat in the UK must have seemed less serious. But, by 1987, the number of people with AIDS in Britain had grown to a thousand, and the development of HIV testing in 1985 meant that the virus had been detected in the blood of thousands more.

Still, the reassurance offered by Bradford Gay that this disease was neither a ‘gay plague’ nor a death sentence still resonates today. If the TV drama It’s A Sin shocked younger viewers with its portrayal of a terrifying tunnel of British history, from which not all gay men and their friends emerged, it’s because they’ve grown up in a time of better medical help and wider understanding.

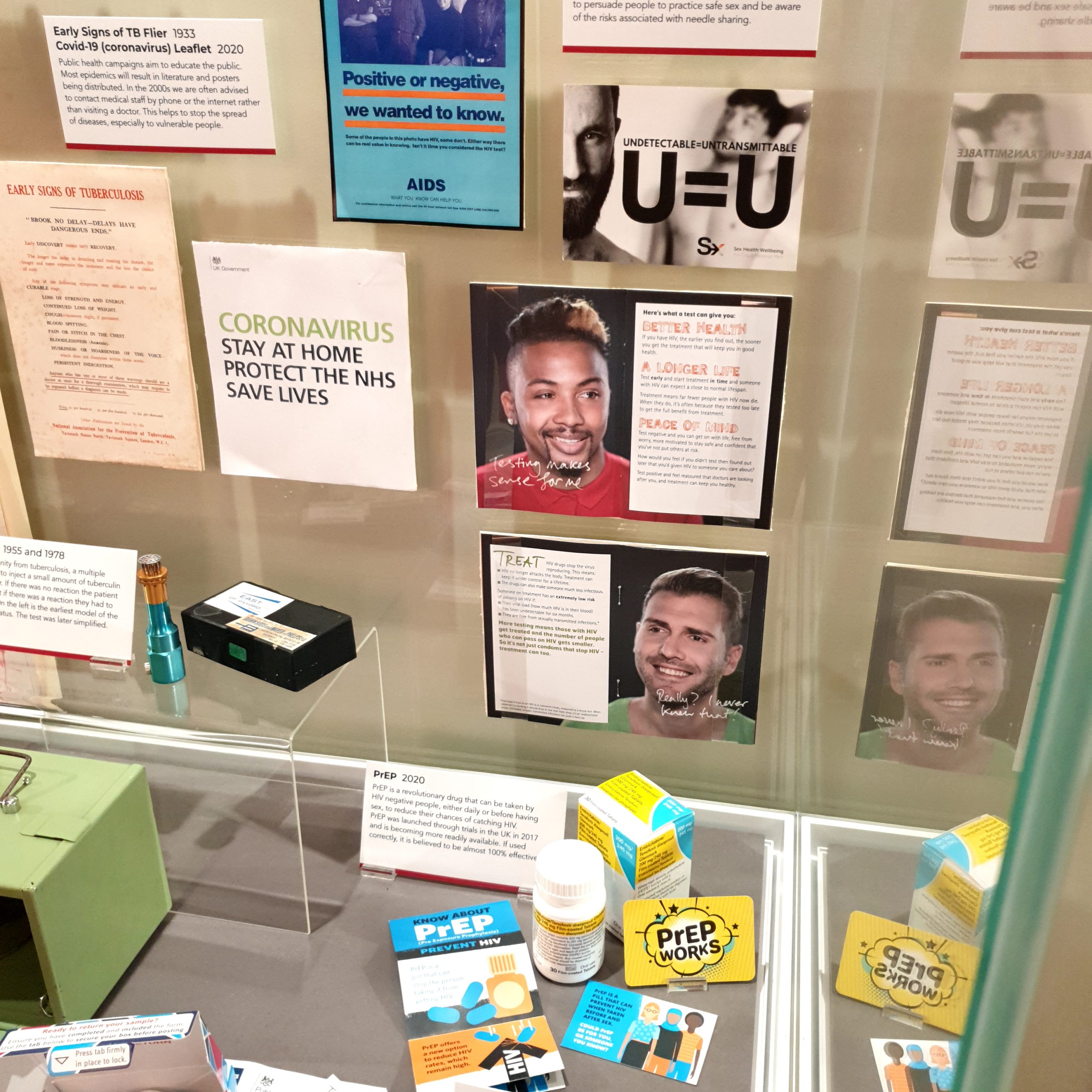

Objects on display at Thackray Museum of Medicine from LGBTQ+ oral history project ran by West Yorkshire Queer Stories and Yorkshire MESMAC

The period took a harsh toll even on those who survived it, as the recent West Yorkshire Queer Stories project found when it interviewed LGBTQ+ people from across the region about their lives and experiences. Historical stigmas had proven hard for some to shake off, while for others the bad memories were those that remained among the most vivid. Mick remembers:

“There was a guy in north Leeds on Street Lane who was stabbed [and] there was a rumour that he was gay. And so first of all the ambulance crew turned up in full biohazard-type stuff, and you can sort of understand it – there was that fear – but what was a bit more shocking was that the Council then turned up an hour later and blow-torched, with flame-throwers, the entire grass verges for 300 yards either way.”

Stories like this made Mick determined to raise public awareness around AIDS myths, and he went on to mount powerful local demonstrations and campaigns alongside members of the pressure-group ACT UP Leeds. Many others joined in, even if the shame of being gay meant they did so without coming out, as Mark explains:

“I remember a guy going on like a Question Time-type thing arranged specifically on AIDS, arguing that being gay should be made illegal again, so there was quite a lot of negativity. So it was scary in that sense but, on the other side of it, it did activate me as well … It gave me a fight to join, a way to openly fight against public hostilities against gay people without coming out … If I did come out, I would be coming out into a really hostile environment.”

Support was slow to come from authorities and explicitly banned in schools under the government’s Section 28 legislation. Within queer communities, however, solidarity and friendship kept hope – and people – alive. Sean looks back on a friend he eventually lost but whose memory he still holds dear:

“I think, like a lot of gay men at the time, he had problems with his sexuality. It wasn’t acceptable; he came from a working-class background, his family didn’t want him to be gay, and he found it really hard to cope with it. And he contracted HIV at a time when there were no treatments available. And I remember him coming round to see me, and saying, you know, ‘I’ve got HIV’. And then it was a death sentence. And I remember him saying, ‘The reason I kept talking to you is cos you didn’t burst into tears. You just said … Are we going for a drink then? Cos you’re not dead yet! Let’s get on with it.’”

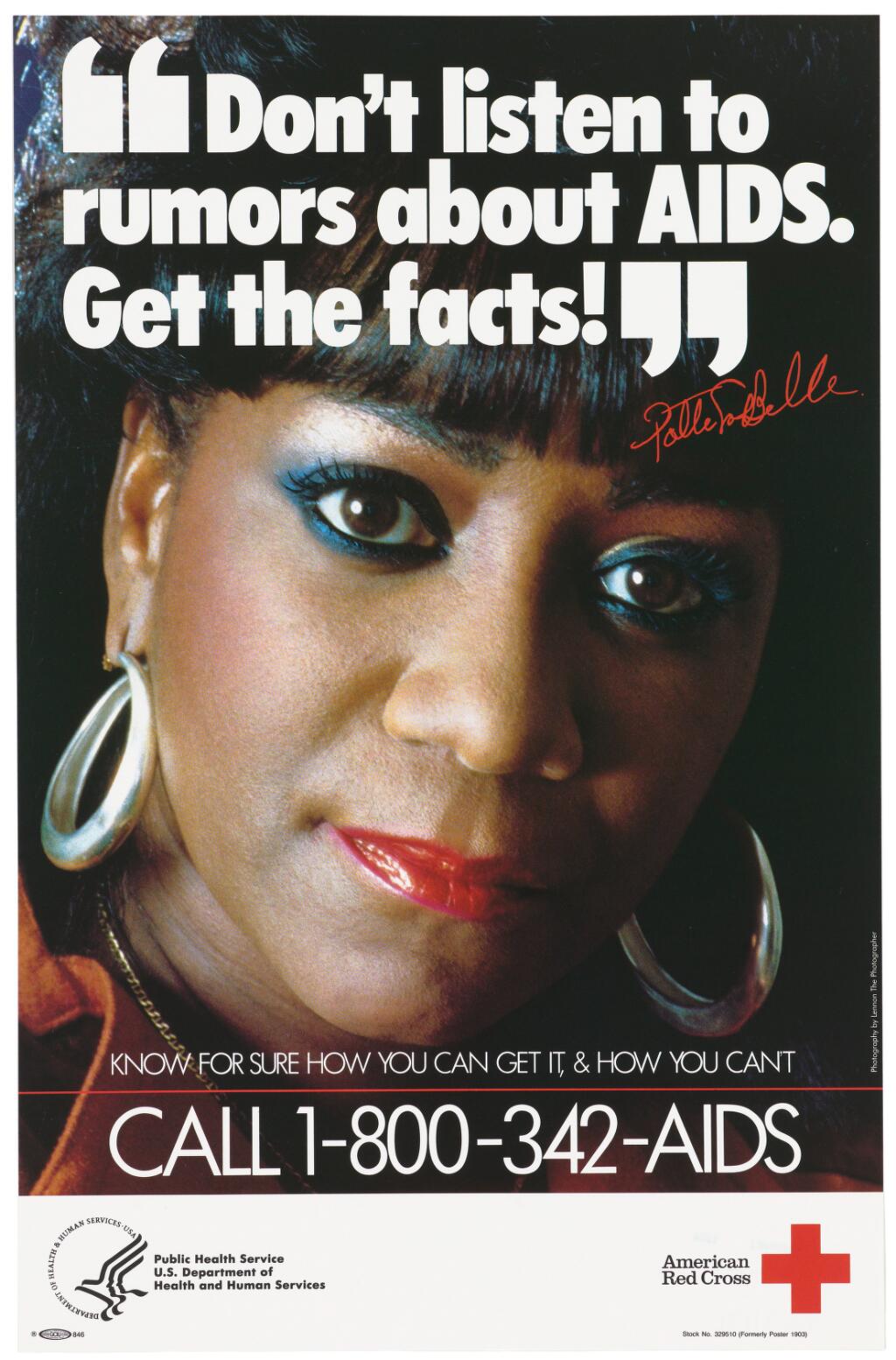

1980s AIDS poster featuring Patte Labelle tackling misinformation (Wellcome Collection)

Gay Switchboards, described as quite literally a lifeline, were established by gay and lesbian volunteers to promote health, combat misinformation and keep the isolated in touch. Stigma around even these services remained, from the Leeds University porters who refused to handle keys used by switchboard staff, to the Bradford counsellors who grudgingly shared space with an answerphone locked in a filing cabinet. But the commitment – like the community itself – ultimately prevailed. John reflects:

“Back to 1988, a big year for me, and the birth of my nephew. I was diagnosed [with HIV] a fortnight before he was born. I clearly remember sitting in my car in the hospital car park waiting to go in and see the new baby and proud parents. In the car, I was quietly crying. The tears were rolling down my face as I was thinking that a new life had just come into the world while I should be preparing to leave it. But, thirty years on, funerals are few and far between. The pills do work. The doctors know how to treat us. It’s not a death sentence to get a positive diagnosis.”

New cases continue, of course, to be diagnosed. Fresh tears are shed and new myths are spread. We’ve grown used to calling our current times uncertain but, for queer communities who lived through the 1980s, they’re not unprecedented.

HIV/AIDS-related objects at Thackray Museum of Medicine

Notes

AIDS/HIV statistics are taken from:

- ‘Surveillance of AIDS in the United Kingdom’, British Medical Journal, volume 295, 5 December 1987, archived at: https://www.bmj.com/content/bmj/295/6611/1466.full.pdf

- ‘30 years on: people living with HIV in the UK about to reach 100,000’, Health Protection Report, volume 5, no 22, 6 June 2011, archived at: https://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/20140714095642/http://www.hpa.org.uk/hpr/archives/2011/news2211.htm

Surviving copies of Bradford Gay are held at the West Yorkshire Archive Service.